SPECIAL

VALUE TO THE OWNER

HEADS

OF COMPENSATION

Special Value to

the Owner can be considered as the sum of the following parts:

- market value

(mv)

- severance

damage (s)

- injurious

affection (ia)

- consequential

damage (c)

- less any

betterment or enhancement (b).

That

is:

special

value to the owner = mv + s + ia + c – b

Each

head will be considered in turn.

MARKET

VALUE

Market

value is the

value of the subject land according to the willing

buyer willing seller theory as

defined in

Spencer

v Commonwealth (1907)

5 CLR 275. The value must be determined according to the highest

and best use (Maori Trustees

v Min

of Works (NZ)

[1958] 3 All ER 336; Dangerfield

v Town of St Peters

(1971) 129 CLR 586).

SUBSEQUENT

SALES AND EVENTS

Subsequent sales and

events provide evidence of the effect that the public work has on any

remaining lands. Therefore, such sales can be used as evidence of

whether or not the owner has suffered a loss greater than market

value (Daandine Pastoral Co v Comm of Land Tax, (1943)

The

Valuer, October, 1943). For example, subsequent sales were admitted

as evidence of the damage caused to a business in Bennet v Comm

for Railways (1952) The Valuer, Vol 12, 169. Subsequent sales are

also evidence of market value if there has been no major event

between the date of resumption and the date sale that would affect

its comparability.

VALUE

TO THE ACQUIRING AUTHORITY

In some resumption

cases, the land has Its highest value only for the use to which the

acquiring authority wishes to put the land. For example, the local

authority resumes the only high hill suitable for water supply

purpose for that purpose (The Rajah case (1939) The Valuer Vol

6, 331). In that case the Privy Council held that market value is the

amount that would have been agreed upon between the owner and the

acquiring authority in amicable negotiations under the willing buyer

willing seller theory. In this case, since the owner knows of the

special value to the authority, he would only agree to a price set at

that value.

A similar decision

was made in Geita Sebea v The Territory of Papua (1941)

67 CLR 147, The Valuer, Vol 7, 25 where land was acquired by the

Territory for a new airport. The acquired land was the most suitable

for airport purposes because an airport had already been constructed

on the site. Held by the Privy Council that the value paid to

Geita Sebea should include the existing airport facilities

despite the fact that the Territory was the only possible user.

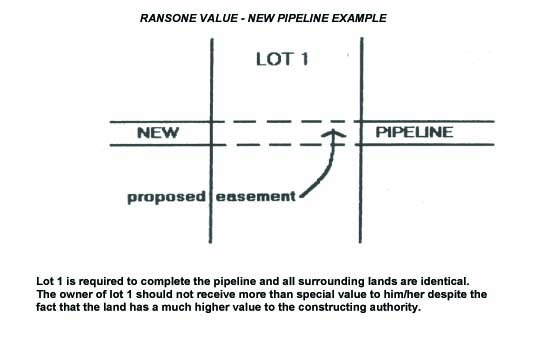

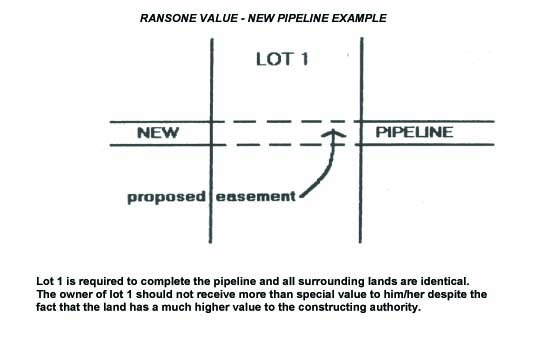

"RANSOME

VALUE"

The affected owner

cannot hold out for a "ransoms value" even if he/she is the

last person required to sell the land so as to complete the public

works.

DIAGRAM - PIPELINE

EXAMPLE

THE

"POINTE GOURDE" PRINCIPLE

The points gourds

principle is that the market value so determined cannot include

any increase or decrease in value caused by the scheme underlying the

acquisition (Points Gourde Quarrying v Sub Intendant ofCrown

lands (1947) AC 565, 572).

The principle is

usually expressed in the relevant legislation for example, s63(a)

Public Works Act (WA). The Australian approach has been to attempt to

apportion that part of any increase in value arising from the public

work and disregard that increase, rather than to only disregard any

increase in value where the whole increase is directly attributable

to the public work (Crompton v Comm of Highways (1973) 5 SASR

301; Housing Commission v San Sebastian (1978) 20 ALR 385;

Emerald Quarry v Comm of Highways (1979) 24 ALR 37).

A typical statutory

statement of the principle is in the Land Acquisition Act (NSW) 1991

as follows:

S56 (1) In this

Act:" market value" of land at any time means the amount

that would have been paid for the land if it had been sold at that

time by a willing but not anxious seller to a willing but not anxious

buyer, disregarding (for the purpose of determining the amount that

would have been paid):

(a) any increase

or decrease in the value of the land caused by the carrying out of,

or the proposal to carry out,the public purpose for which the land

was acquired; and

(b) any increase

in the value of the land caused by the carrying out by the authority

of the State, before the land was acquired, of improvements for the

public purpose for which the land is to be acquired; and

(c) any increase

in the value of the land caused by its use in a manner or for a

purpose contrary to law.

(2) When assessing

the market value of land for the purpose of paying compensation to a

number of former owners of the land, the sum of the market values of

each interest in the land must not (except with the approval of the

Minister responsible for the authority of the State) exceed the

market value of the land at the date of acquisition.

The effect of the

proposed public work was well considered in Woollams v The

Minister (1957) 2 LGRA 338. This case concerned the compulsory

taking of farm land for the building of Warragamba dam, part of

Sydney's water supply. Hardie J held that the market value paid to W

was normal market value free of any depressing effect caused by the

market's knowledge that a dam would soon be built in the valley. A

proxy for that amount was found by reference to sales of comparable

but non affected lands in valleys nearby.

MARKET

VALUE AND LAND USE CONTROLS

Problems occur when

the acquired land is reserved for a public purpose under state law.

Market value will be determined according to the restrictions

contained in the reservation or according to the land use before the

acquisition or reservation.

A valuation based on

the restrictions of the reserve/resumption is unfair if the land has

been resumed for THAT purpose. Where the reservation or resumption is

part of the SAME overall scheme, the Pointe Gourde or Woollams

principle applies. This ensures that the effect of the

reservation or resumption on the market value of the land is ignored.

However, where the reservation of the land and subsequent resumption

are unrelated, the valuation must be according to the reservation (re

Housing Comm of NSW v San Sebastian P L (1978)140 CLR 196).

Under current law

there is no simple process for resolving this question and each case

is determined on its merits. However, in other countries, two systems

have developed to overcome the problem:

- UNDERLYING

ZONES NEW ZEALAND

Under this system the

planning authorities are required to nominate the underlying

zoning of land subject to a planning scheme at the time of

publishing the scheme. In New Zealand, planning schemes are

advertised and public comment is invited with regard to the

underlying zones.

- CERTIFICATES

OF ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT – UK

Under this system

certificates of alternative development allows for either the

claimant or the acquiring authority to apply to the relevant planning

authority for a certificate setting out the purposes for which the

land may have been used, had the land not been reserved.

See

SEVERANCE DAMAGE

See

INJURIOUS AFFECTION

See

CONSEQUENTIAL LOSSES

BETTERMENT

OR ENHANCEMENT

Betterment is an

offset against the compensation heads covered above for any increase

in value to the residue lands as a result of the proposed public

works. Betterment can be thought of, as the reverse of

injurious affection. For example:

s55(f) any

increase or decrease in the value of any other land of the person at

the date acquisition which adjoins or is severed from acquired land

by reason of the carrying out or the proposal to carry out, the

public purpose for which the land is acquired Land Acquisition

Act (NSW) 1991.

Betterment can be

greater than the compensation otherwise payable. For example, in

Brell & Anor v Penrith City Council(1965)11 LGRA 156 it

was held that the increase in value of the remaining retail land

caused by the construction of a public car park at its rear, was much

higher than any other losses and therefore, without trying to

quantify the increase, no compensation was payable. In the same case

it was held that betterment was the amount emanating from the total

carpark, not only from the part taken. However, in CBC v Penrith

City Council (1970) 19 LGRA 156 it was held that compensation was

payable because the land before resumption had a high value for

redevelopment purposes so that the loss to the owner was greater than

the betterment.

SCHOOL

SITE

In Moore v The

Minister (1962) 18 The Valuer 245, it was held that no

compensation was payable to the affected owner of land suitable for

residential subdivision because the building of the school would add

more value to the residue lots not yet sold, than any loss or damage

suffered by the plaintiff.

DRAINAGE

EASEMENT

In Glen &

Anor

v Sutherland Shire Council (1965)18 The Valuer 574, it was held

that no compensation was payable for the resumption of a drainage

easement over the subject land because the increase in value to the

residue brought about by better drainage was more than any loss in

value. Before resumption, the plaintiffs could not build on the land

whereas, after resumption they could.

7